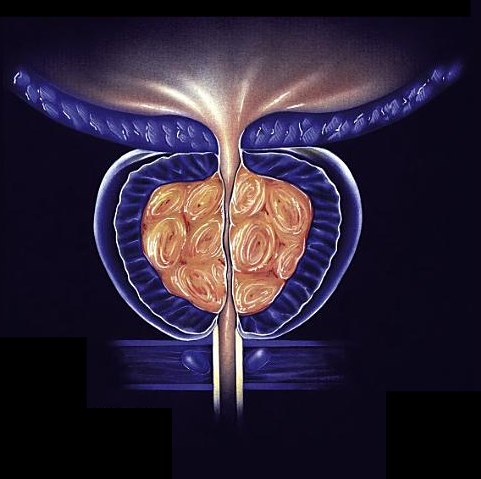

On and off for about 15 years I’ve had blood in my urine. I’ve also had trouble peeing and taken drugs to make it easier. Recently my PSA reached abnormal levels so I had an MRI which showed my enlarged prostate has lesions which will be biopsied next week.

The process involves inserting a catheter camera up my urethra and a needle through my peritoneum to biopsy the lesions. Because I have six arterial stents, anesthesia is a concern as is internal bleeding and resultant pain, but beyond a scary cancer diagnosis, my greatest fear is reliving the last ten years of my father’s life.

When I first saw him in hospital surroundings, he looked like a 69 year old boy. As he peered out from his blood spattered sheets tucked tightly around his chest in his Johnny coat, I asked how he was. “Great,” he answered stoically and every time since until I stopped asking. A glance out the window meant it was time for me to leave.

Soon after my formerly dashing dad returned home from radiation, he began to loose his hair then quit his life-long career as an architect. Then his body changed. Hunched over, he began wearing suspenders and twelve years later he died. He was never happy-go-lucky but those years were the pits. One cancer led to another and numerous treatments left him distant, dour and toxic, especially to my mother.

My parents’ drinking and subsequent loose tongues dissolved their relationships with each other and life-long friends. When cancer coupled with his personality made it impossible for anyone to relate my father, they were alone with each other ’till I moved in.

I’ll never really know the effect my presence had during that time but my mother’s shrieking and incessant complaining about my father’s aloofness drove me nuts. To her, his table-top full of bedside pills was intentionally arranged to silence her. With no one else, she’d unload on me, obsessing about how her misery might end ‘till she became sullen and silent which lasted for days, then years.

In his seventies, when my father could no longer climb stairs, I moved him into their living room. When I offered to watch TV with him or massage cream into his large ademic calves, he acted incredulous and waved me away as if I’d suggested incest.

No matter how morose he behaved with my mother and I, my dad would perk up for female nurses. His charisma had them convinced we must be charming too, but when they learned we weren’t, they’d curtly tell us what we needed to know about his condition then wink at him before leaving. “No wonder he has cancer,” I imagined them muttering as I poured my mother and I more wine .

We’d all tried anti-depressants and various forms of self-help but by the time my father got sick there was no changing any of us. I spent his last decade mostly with or near my parents. The next ten years I dealt with my mother’s dementia until she recently died at 96, so the prospect of being free of them after another twenty years felt like a brief reprieve until the pandemic.

Historically I’d soothed my demons with creativity, especially with music but since my parents’ death, then Covid, I’d rather draw swimming pools than vocalize or get my hands operated on for Dupuytrens contracture so I could tinkle the ivories.

Though abruptly letting go of life-long passions seems strange, after scheduling this biopsy, every choice I make feels crucial as new fears and memories of my father traipse across my mind.

Two days ago, before my MRI results, I experienced another reprieve – my second Covid vaccination. Yesterday, I felt very ill from its effects when I learned I needed this biopsy.

Today I subscribed to an incredibly powerful pool design CAD program monthly, rather than anually in preparation for a busy yet potentially fickle spring.

I’m neither one of my parents, yet am. I’m sure they worried about becoming their parents too but I’m hoping this sudden magnification of life choices eases me into who I’m becoming in good ways rather than simply exacsorbating deep neurosis like the effect my father had on my mother’s early onset dementia.

I know how common and perfectly treatable prostate cancer is, but there’s no being perfectly rational. I can pretend to be unconcerned but the “pain in the ass” of my looming prostate biopsy haunts with memories of when my dad first mentioned his.

I hope I never go through what he did and remind myself it’s a different time. Today’s treatments are far less debilitating and whatever’s going on with me might not need treatment at all. When I recall those I’ve known with cancer, I’ll do so with reverence rather than panic and if I can’t find someone to talk to, I’ll write.

I won’t let fear steal any more of my life. I’ll learn my new CAD program to help sell swimming pools more enjoyably and if I can’t, I’ll call friends from the road and whether or not they interest, comfort or annoy me, I’ll liberally indulge in gallows humor. I’ll cherish my kitties and my yard and use clients to forget about myself while helping them build there own paradise.

I’ll remind myself to “talk to worms on the street,” but most of all, I’ll appreciate my adorable husband who I’ll never wall off no matter what, and if this biopsy shows nothing to worry about, I’ll write about that too.

You won’t wanna miss my photo montage.

Leave a comment