After discussing suicide with my mother throughout her life, I was surprised she waited ‘til her mid-nineties to lunge headfirst from her wheelchair. Though a lifelong depressive irritated by everything, I thought my mother was too spineless to do it ‘til she did.

Though she never sought therapy, she discussed killing herself like others did plastic surgery. “Why not,” she said pulling on a cocktail, intently watching a Jack Kevorkian interview wondering why anyone should have to wait for terminal illness to receive a satisfying drip.

“Everyone should have the right pill and not feel guilty for taking it,” she slurred at dinner while my father and I chewed. Though SSRIs were just becoming available, my mother refused to take them. She wore her dissatisfactions on her sleeve, traveled and thrift shopped with them, dressed accordingly and worked her misery into lousy paintings. She was the only person I knew who could plant a tomato and have it shrink. She only read feminist authors and for all anyone knew including my father, she might have been a lesbian.

Virginia Woolfe’s final note after realizing mania had returned said she owed all her life’s happiness to her husband. Though my mother could no longer hold a pen and despite my parents’ dubious love story, I preferred imagining she felt something for us the day her forehead hit the concrete. Despite being unable to remember either of our names, I guessed she loved her family though she never mentioned it even before officially loosing her marbles.

Unlike her favorite author, my mother’s diaries were mired in chronicling banal dreams. Our Newfoundland dog laying in the yard or my father playing tennis barefoot revealed little of her interior life. A week before she died, while she could still speak, after dutifully telling her I loved her, all she said averting her gaze from the hospice nurse toward the wall was, “do you?” I would’ve appreciated eye contact or a gentle smile instead of her typical candor, but she’d never been a mincer of words. A wry Canadian who’s best quality was her physical resemblance to Joni Mitchell, my mother’s only true talent seemed to be unhappiness, yet even frail with dementia she gave the impression there was so much more.

She knew she wasn’t strapped in when she leaned forward. Normally she’d slide to the floor unbound then create a scene moaning like a desperate invalid but when I got the call, I knew what she’d done. “Not again,” the aid said as several of them wrestled her back into her chair and a Ping-Pong ball sized lump began to emerge from her forehead. “Good for her,” I thought on the way to the emergency room praying she’d hit hard enough.

Though tests showed no neurological damage, as an aid explained what happened, thanking God while combing her greasy hair, I knew my mother’s end was finally near. From then on as she staired into space refusing to eat, it was only a matter of time before we’d be free of each other or so I thought until years after her death my desperate need for a different path inspired this writing.

The dark months after my father’s death were pivotal. She could’ve easily ended her life then with alcohol and Diazipam but chose not to as if auditioning me for his former role. Though I’d become enmeshed in managing my parent’s dramas, I lived forty minutes away. There’d been evidence of my own life, until attending to theirs made mine impossible. My mother ranted about my father while he was alive then adrift without him, she ranted about that too. Failing to make her happy did little to keep me from trying and I did everything I could including drinking too much to help her feel less alone.

I thought she’d attempted to kill herself one night during those first few months when I found her sliding around her kitchen floor drenched in Burgundy, but after polishing off a bottle, she’d merely tangled with her first-ever box of wine. She figured out how to open the spigot but didn’t know how it closed and too drunk to upend it, she let the whole thing empty onto her white kitchen floor then called me like its victim.

Had she called the front desk for help, she would’ve been kicked out at the retirement village my father picked for her to die in. Management had already let me know she was no longer welcome at the bar. I’d delivered the boxed wine instead of the Vodka and Gin I’d poured down the toilet the week before in a vain attempt to wean her off booze like my father had tried to unsuccessfully.

Shrieking and other combative behaviors threatened to get her permanently medicated so I told her to stay at home and call me if something went wrong. I’d taken away her car keys after she returned dragging a bumper but when cops found her on her way to a liquor store riding her “Jazzy” in a snowstorm wearing a light sweater, her independence slammed shut.

With more eyes on her in assisted living, her ability to kill herself would be severely compromised. We’d discussed it so often; it seemed a viable conversation starter but not the kind of thing one brought up at Bingo so my mother stayed in her room watching depressing TV news and kept her mouth shut at meals.

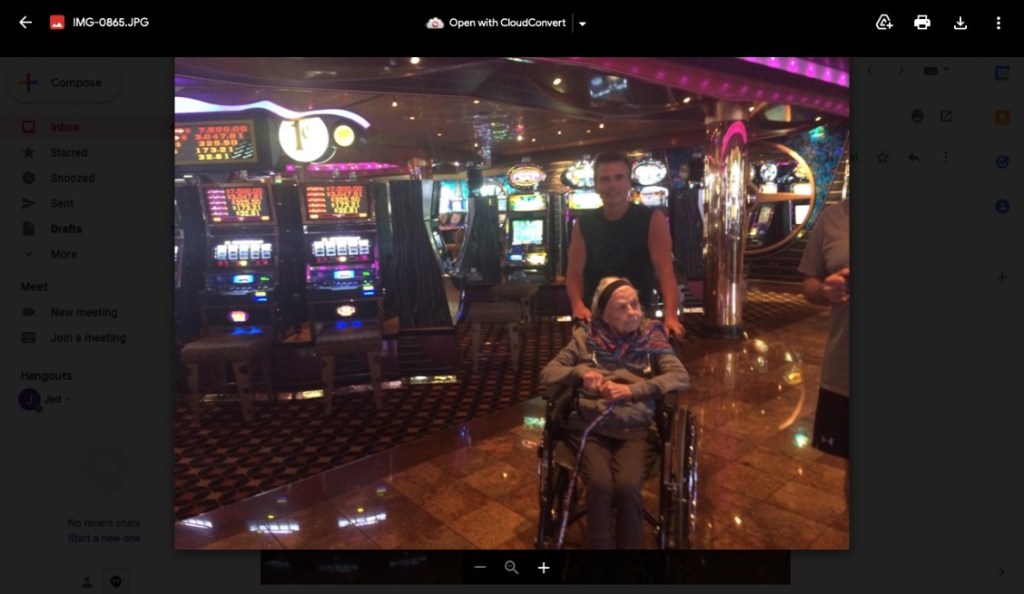

When I took her on a Caribbean cruise, I told her I couldn’t throw her overboard ‘cause there were cameras everywhere wink, wink. “I’d be glad to swim you into deep water on a remote beach Mom,” I said, pretending it was a joke.

I could always reach her with gallows humor and morbidly wheeling her around nursing home courtyards the last years of her life kept us bonded. After she broke her hip, never walked again, and began pleading to be euthanized I told her, “All you have to do is lean forward mom,” a few times kissing her on the forehead assuming she’d never have the guts, but I was wrong.

It’s taken my entire life and years since my parent’s passing for me to begin to understand life-long suffering. My father’s mother lived a similarly troubled life. I hope this writing illuminates my family’s fascination with suicide and frees me from my own disturbing thoughts, but so far, my mother’s courage to finally kill herself still makes me proud.

Thirty years earlier in the dead of winter, while they lived beside a gorgeous tidal river anyone else might kill to live on, my mother stormed toward it drunk screaming “rocks in the pocket.” We knew from hearing her so many times all about the technique Virginia Wolfe used to remain submerged as my father and I joined her distraught on the wall with another glass of wine. She gladly accepted it and the three of us dangled our legs over the black water alone together, unable to sit close enough to warm our staunch Irish, German and Russian Jew blood any other way. Staring down at imagined phosphorescence oblivious to the cold, perfection in my family was only achievable in nature with enough alcohol to obliterate our bleak DNA.

My mother sneered at the aquarium fish in her first assisted living facility. She derided its decor, dizzying patterns in the maze of carpeted hallways and its perfectly mulched flower beds but pointing out suitable branches to dangle from using a landscaper’s hose made her smile. We play-acted drowning while exercising in her therapy pool and discussed fending off Heimlich maneuvers though by then chicken bones were no longer on menus.

“They’re not going to like this mom,” I said toweling up the blood-red Franzia from her kitchen floor unable to lift the stains from the grout. “What about that,” I asked pointing at my mother’s medicine cabinet as she wailed in the next room knowing where she was heading. Her medical supervisor opened a zip lock. “In they go,” she said.

Seeing an array of possibilities tumble into the bag, I thought my mother’s life would change dramatically but I was wrong. Nothing including her inevitable sobriety had any effect on her mood. She continued to suggest flinging herself into traffic but without alcohol, food was her only comfort. Instead of starving herself, she grew a pot belly.

Whenever she saw me, she continued to ask for creative ways to off herself out of habit. I said I hadn’t smuggled anything in, but a tall building residents frequented for the view might offer some possibilities. I took her there on all my visits to familiarize her with the route. “You can see Long Island from up here any time you want Mom,” I told her before she broke her hip. She’d climbed plenty of fences and could certainly manage a railing I thought when I began realizing all she ever wanted to do was suck me dry.

My father warned me of this before he died. He left plenty of money for her care. “Turn your back. Save yourself. She’s crazy,” he’d told me emphatically on his last trip to the hospital, but I’d never once taken his advice and wasn’t about to start at his deathbed. If he couldn’t abandon her without dying, how could I?

Leave a comment