I first heard my father had a girlfriend from my mother who spilled the beans while they perused retirement village catalogues. Trying to address lifestyle changes that his failing health imposed, they’d visited a few places when I heard my mother ask what kind of community he’d have chosen for him and “Lela” to live in. “Who’s Lela,” I asked helping myself to their wine.

I’d moved into his office on the third floor of their house and came across online correspondence from some woman named “L” on his computer but had no idea who she was. He could no longer stand up from severe edema and lived in a hospital bed in the living room, but even healthy as a horse he refused to be probed. He didn’t discuss his childhood as the adored son of dysfunctional alcoholics which I found out about from his angry sister. His inner life was a mystery. His girlfriend’s concern for his deteriorating health was touching. I was glad he had someone who cared about him as everyone else in my family was incapable of nurturing anyone including ourselves.

While preparing to move them while weeding though his stuff, I found out he’d been a backup bomber in Nagasaki, which explained why he changed the subject whenever World War II came up in conversation. No one could imagine how the flash affected him or dared suggest it might have resulted in medical or emotional issues.

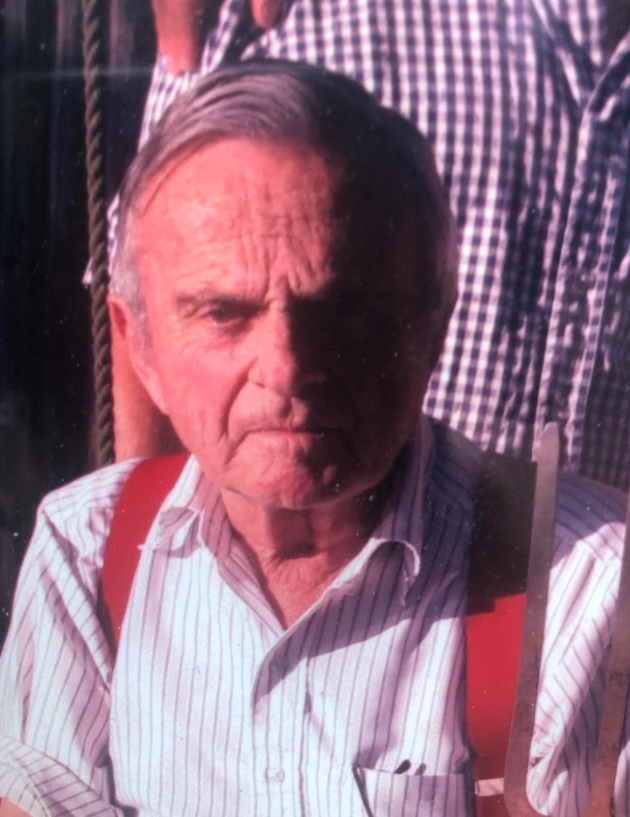

He’d been a good-looking spoiled brat before the war and though the trauma tempered his enormous ego enough for him to appear affable, my strong, charming father was an insensitive know-it-all who cracked my rib twice subjecting me to his awkward hugs.

After a stellar career as an architect, at sixty-five he was going nuts in retirement when having his hip replaced, cancer turned up in his bone marrow. Preventative treatments led to a twenty-year bout with various carcinomas, heart bypass surgeries, joint replacements, and my own concern about inheriting his worrisome DNA.

After receiving a midnight call from the hospital that his blood pressure was dropping, I arrived moments after his last breath to a Renaissance painting. Watching him turn angel-pale before my eyes, his arms wide open and palms aimed heavenward, I flopped on him in tears. “Why weren’t you ever this relaxed while you were alive you bastard,” I cried to sooth myself while pipedreams of ever bonding with him died as well.

No longer interested in designing shopping malls, ill-tempered, weary of home projects and endless days with my winey mother, after his first cancer treatment he stoically shaved his head and entered the healthcare system with open arms. Turning on his false charisma while being waited on, hospitals treated him like his doting parents had.

My damaged mother was incapable of caring about anyone. She’d joined the service to escape her family. Her strict German father, obsequious mother, and sexually abusive brother destroyed her trust so by the time she met my father at a USO dance, underneath her milkmaid looks was a dutiful zombie, willing to marry rather than return home.

“It’s what couples did back then,” my father said. “And still do,” I added mystically, after my four failed relationships by age forty with nowhere else to go. Pouring more wine, I realized the arrangement suited all three of us. My unstable mother needed therapy so who better to talk to than her suicidal son? She sneered with contempt at my sensitive Borzoi who squatted and peed with fear.

“The prodigal son returns,” my bald father said unwilling to see me as a chicken returning home to roost. Tipsy, he greeted me with open arms challenging me to a hug. I smiled back wincing, pointing to my unhealed ribs then went up to his former attic office to make myself a shameful nest. Watching the sun descend, realizing the depths I’d sunk to moving back with my parents, I turned and went down for cocktails as I would for the next five years until I couldn’t take their bickering any longer.

My normally dower father flirted with hospital nurses then returned home, retreated to his bed, and watched PBS all day. My spartan mother who’d always resented being a wifey, complained to me about her life with him on our nightly beach walks drinking wine from Evian bottles. I mediated their fights, wrote music, took acting lessons in Manhattan, and visited sex clubs after class.

After five miserable years living with them, by forty-five I’d had a heart attack and a hip replacement but unlike my father, whoever tossed my femur in the wastebasket never mentioned cancer. There was a smugness in his voice when my father announced his. “What does this mean,” I asked “Well,” he said rolling his eyes, “it means after I recover from hip surgery, I’ll feel like shit, then go bald,” he replied to my dim-witted question cashing in on his diagnosis to get the attention he craved.

After writing a musical with lyrics he admired, rather than compliment me, he accused me of plagiarism because he thought my own lyrics were mawkish. Clearly, he never understood me, but I’d found someone unlike anyone I’d ever met; someone I could finally talk to who’d become my husband, so why did I wail so desolately scattering my father’s ashes?

Leave a comment