“And the women who let them,” my lesbian friend quipped when I mentioned starting Laura Bates’ book “Men Who Hate Women.” Her spontaneous response caught me off guard, and though we both laughed nervously, her words would haunt me through my journey with Bates’ unflinching exploration of modern misogyny.

As a gay man approaching seventy, I’ve spent a lifetime navigating the complexities of prejudice and power. I thought I understood hatred, having faced it in schoolyards and society’s shadows. But Bates’ book forced me to confront an uncomfortable truth: sometimes those who experience discrimination can harbor our own hidden biases.

My first realization came while reflecting on my childhood. As a bullied kid desperately hiding my truth, it wasn’t just the boys’ fists I feared – it was the cutting words of girls who sensed my difference. My mother, herself a survivor of sexual abuse, showed affection to my sister but kept me at arm’s length. Female teachers urged me to toughen up, their words carrying the weight of generations before them. These experiences left invisible scars, shaping my unconscious attitudes toward women in ways I’m only now beginning to understand.

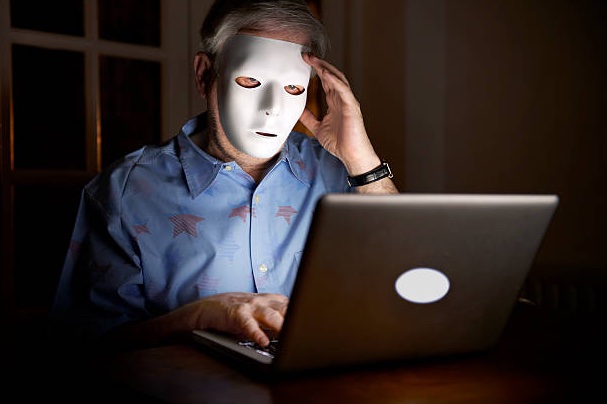

The internet era brought new dimensions to these old wounds. In 1999, I found refuge in gay chat rooms, where traumatized, lonely men could share their stories without judgment. It felt safer than bars, until the darkness crept in – suicide threats, anonymous harassment, the reduction of human connection by nude photos and abbreviated desires. I retreated to the relative safety of Facebook, believing I’d found a healthier space for self-expression.

Then came Trump’s reelection. Like many, I felt defeated. My husband and I retreated into our bubble, telling ourselves we were lucky to have each other. We could live out our lives in relative peace, ignoring the dissolution of rights happening around us. I justified my withdrawal from political engagement by turning to classic literature, claiming it was healthier for my temperament to mine novels for wisdom than to watch cable news.

But when a friend accused me of choosing “ignorant bliss,” her words stung with truth. Was I, in my comfortable withdrawal, becoming complicit in the very systems of oppression I’d fought against in my youth? Bates’ book forced me to confront this question. Her deep dive into the world of online misogyny – from incels to alt-right extremists – revealed patterns of hatred and alienation disturbingly similar to what I’d witnessed in childhood and in those early chat rooms.

Reading about the normalization of violence against women, I recognized how easy it is to become desensitized to hatred when it doesn’t directly target you. Each chapter of her book challenged my assumptions about my own role in perpetuating harmful systems. When she described how misogyny intersects with other forms of discrimination, I couldn’t hide behind my identity as a gay man anymore.

My lesbian friend’s comment about women’s complicity suddenly took on new meaning. Perhaps she, too, saw how marginalized groups can sometimes participate in their own oppression. The way some women internalize misogyny mirrors how some LGBTQ+ individuals internalize homophobia – a survival mechanism that ultimately serves the status quo.

This recognition has pushed me out of my comfortable silence. At nearly seventy, I may not march in protests anymore, but I can’t retreat into ignorant bliss either. The answer lies somewhere between – in having difficult conversations, in examining our own biases, in supporting those doing the hard work of social change.

As Bates argues, the normalization of hatred is perhaps its most dangerous feature. Whether it’s misogyny, homophobia, racism, or any other form of bigotry, our silence and withdrawal only serve to maintain these systems. True change requires us to look in the mirrors we’ve been avoiding.

Today, when my husband and I walk down the street waving to strangers, it’s no longer just an act of defiance against potential hatred. It’s a reminder that visibility matters, that engagement – even in small ways – helps crack the foundations of prejudice. And when I catch myself falling into old patterns of judgment or withdrawal, I remember my friend’s words about “the women who let them” and challenge myself to do better.

My path forward isn’t in hiding from uncomfortable truths or in performative activism. It’s in the daily work of examining my own heart, challenging my assumptions, and staying engaged with the world around me – even when it would be easier to look away. After all, the opposite of hatred isn’t just love; it’s understanding, engagement, and the courage to face our own reflections in the mirrors we’ve been avoiding.

Leave a comment