My father gunned his impatient BMW toward I-80, determined to get me past the George Washington Bridge. Stuck in high traffic, the unyielding bridge rivets and dreamlike far reaches of the Hudson River burnished themselves into my psyche. I watched Cochise and his band of scouts on the Palisades, saw Hiawatha leap from a high cliff followed by her faithful bay stallion who couldn’t live without her. The horse’s frantic neighing echoed between each successive grimy girder, still swimming in circles searching for her when the grimy reality of Fort Lee blocked me back. Unwilling to accept New Jersey, I welcomed Hiawatha’s heroic dripping horse with his graceful mane and flaring nostrils as he cleared a barrier onto I-80 and galloped beside me. The stallion nearly lost his footing navigating roadside debris while my father, scanning between tires and exhaust pipes for somewhere to drop me off, kept yelling, “God damn it.”

I slumped in the seat, pulling my oversized jacket across my lap to hide my nubby fingers, casualties of a nervousness that had also worn down my front teeth. The woman taking my license photo weeks earlier had smirked, “Smile,” but I’d gone to great lengths by then to hide these betrayals of anxiety. Clenching my jaw and scowling to look more masculine, I chain-smoked, got drunk and high, and looked demonic in my license photo. Yet I was still too scared to drive on a highway, so after my father dropped me off, I stuck out my thumb and hoped whoever picked me up might offer me something to take the edge off.

I’d been hitching to and from boarding school the year before, so I wasn’t surprised when moments after my father sped away, a Volvo lurched into the shoulder garbage. “Where you going?” the middle-aged driver asked, with a Bud between his legs. “California,” I said like in a movie. “How does Chicago sound?” “Great,” I said, tossing my pack in his backseat. After handing me a beer, he had his hand on my thigh by Parsippany. “Is this okay?” he asked in a familiar tone, but unlike my math teacher, who’d take a long beady-eyed drag of his Parliament before fondling me, when I looked out this guy’s window, he placed his hand back on his steering wheel without a word.

The Poconos rose ahead like a blue wall becoming green. “What the Hell’s a Del Water Gap?” I asked, watching signs flash past. “The Delaware,” he laughed, pointing at the river, “Gateway to the West.” Suddenly stagecoach teams weaved between boulders, oxen trudged, wagons rocked, and leggy dogs loped along the Delaware’s banks. Staring at the river rushing to be somewhere else, I wondered if Lewis and Clark wore underwear, when I realized how much I needed to use a bathroom.

The driver didn’t try to follow me into the branches listing toward the dancing water. I snapped off a spray of impossibly fragrant honey locust but rather than bringing him flowers, I tossed it in the river so some kid in a ghetto downstream might dare to dream. He wasn’t bad looking and we both wore corduroys. He probably had porn and would understand why I bit my fingernails, but I wasn’t ready to settle down.

After a year at my progressive boarding school, I’d been given permission to construct a cabin in the woods – my planned escape from men, boys, girls, fathers, woman and dorms. Before leaving for summer, I’d begun a rock foundation about a mile from campus on moss-covered ledges that would double as lawns. I knew how to tie a rope bed, where to steal windows, buy a cheap tin woodstove. Every board of my imagined 8′ x 12′ box felt like freedom, until exhausted from listening to my driver drone through Pennsylvania, I wanted to leap out out of his car and gallop.

The cabin was just one escape route. April in California was another. Her letters still came with drawings in the margins – disarming kitties and horses like the ones we used to sketch together. Though seventeen by then, her innocent artwork felt like a call for help. “April is selling Sundance,” I’d told my father nearing the bridge, as if on my way to her rescue. The horse wouldn’t let anyone else ride him, had bucked off her boyfriend who was a trainer. I remembered the day Sundance arrived, just before a snowstorm. April and the big handsome bay had danced silently toward me in the falling snow, and I’d never seen anything so beautiful as they loped collectedly between the flat grey water and long white beach. All she did was lean slightly forward and the two shot away percussively until all remaining were foghorns.

Eight hours later, in the outskirts of Cleveland, the Volvo driver paid for a motel and left me in our room to pick up takeout. I showered and, riffling through my stuff, found the daybook my father gave me to journal in. I didn’t want to lie any more than I had to, so I began sketching instead. The next morning, watching traffic rushing to escape itself on the gloomy Cleveland highway, I wondered if anyone cared about anything else and stuck out my thumb anyway.

My parents had been proud of how I’d seemingly grown balls in less than a year at Barlow. After eight years disintegrating at a boys’ school, then getting beat up in a public one, they’d read about Barlow in the New York Times. “It’s saving him,” my father kept insisting. The sixties were over. Everyone was solidly in denial and avoided confrontation. When my mother came across a pair of scanty men’s underwear in my pants pocket, she’d folded them neatly on my bed. Though I was prepared to say they were for swimming in the Barlow pond where everyone else swam naked, I didn’t need to. Even when my father handed me a leather cock ring he’d found on his office floor, I nonchalantly snapped it to my wrist and said, “thanks.”

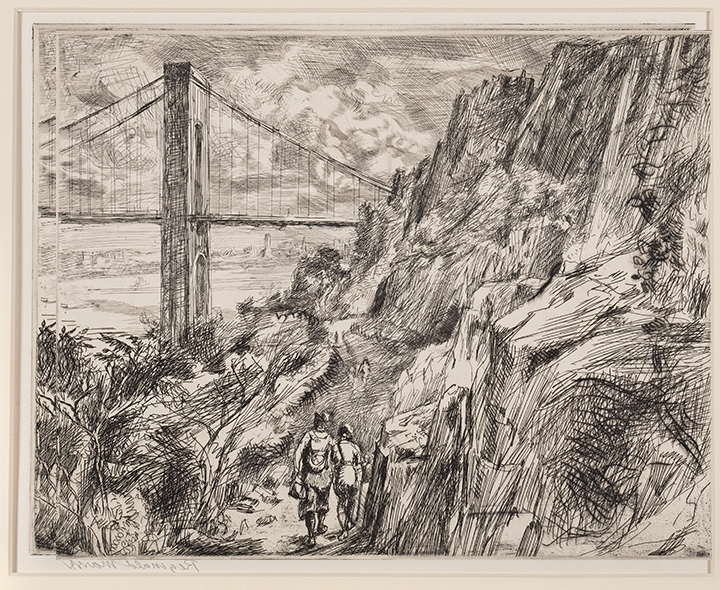

Like so much other shit in my life I wanted flushed away, I couldn’t shake the signs of who I was without appearing guilty. Even my sister Lisa was off hitchhiking around Europe before acting out at college, and my parents were selling their house. Though they hadn’t suggested I leave, they didn’t protest when I announced my plan to hitch across the country at sixteen. Looking at the highway stretching endlessly before and behind me, I knew I was just another thing rushing to escape itself.Etching by Reginald Marsh

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply